- 文献名 -

Discovering professionalism through guided reflection

Medical Teacher, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2006, pp. e25-e31

PATSY STARK, CHRIS ROBERTS, DAVID NEWBLE & NIGEL BAX

Northern General Hospital, Sheffield, UK

- 要約 -

[Intorduciton]

There is increasing evidence (Sox, 2002; Papadakis et al., 2004; ABIM, 2003) that unsatisfactory performance in practice is more likely to be due to unprofessional behaviour, rather than knowledge or clinical skills. At the University of Sheffield, such an opportunity for reflection on professional behaviours arose in the Intensive Clinical Experience (ICE) within the first year of the course.

We validated our professional behaviours outcomes by mapping them against the principles of Duties of a Doctor (GMC, 2001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Duties of a Doctor (from Good Medical Practice GMC, 2001).

・Make the care of your patient your first concern;

・Treat every patient politely and considerately;

・Respect patients’ dignity and privacy;

・Listen to patients and respect their views;

・Give patients information in a way they can understand;

・Respect the right of patients to be fully involved in decisions about their care;

・Keep your professional knowledge and skills up to date;

・Recognize the limits of your professional competence;

・Be honest and trustworthy;

・Respect and protect confidential information;

・Make sure that your personal beliefs do not prejudice you patients’ care;

・Act quickly to protect patients from risk if you have good reason to believe that you or a colleague may not be fit to practice;

・Avoid abusing your position as a doctor;

・Work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients’ interests

Within the postgraduate arena, the tenets of Good Medical Practice have been used to create a multi-source feedback tool to assess a range of generic skills, which cover aspects of professionalism in the workplace (Archer et al., 2005). We wished to use the portfolio approach with the purpose of marshalling evidence about the progress of students towards the specific professionalism outcomes of our course (Challis, 1999).

[Method]

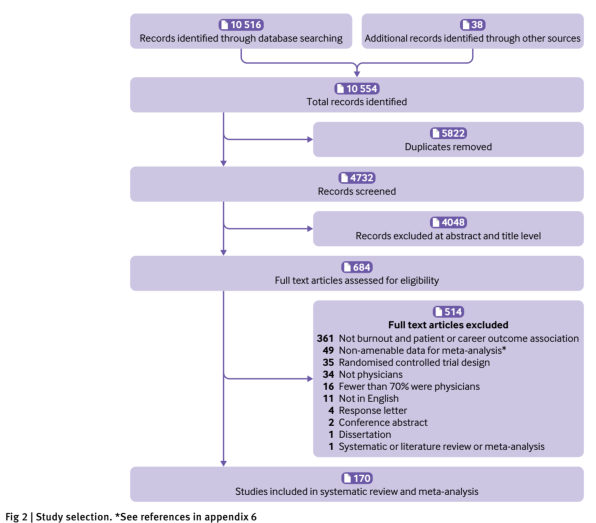

This study aimed to discover the educational impact, validity, and feasibility of the critical incident as an assessment method for a class of students undertaking guided reflection in the context of their first exposure to health and social care professionals at work.

The ‘guided reflection’ method (Johns, 1994; Wilkinson, 1999) was adapted to prepare students to engage in reflective practice (Figure 2). We defined a ‘critical incident’ (Flanaghan, 1953) as any event that challenged them within the context of Duties of a Doctor.

Figure 2. The guided reflection template showing the steps the students had to follow.

1. List the Duties of the Doctor (as listed in Good Medical Practice) to which your incident related

2. Describe the incident in your own words

3. Illustrate the ways in which the incident challenged your values, beliefs or understanding.

4. Describe which learning resources you used to increase your understanding of the issues you described. Which were useful and which were not?

5. Describe how the situation may have been handled differently.

6. What did you learn personally from this incident?

7. What future learning do you plan to do around this incident?

[Outcome measures]

We used two outcome measures to provide data for our study. These were: (1) The quality of student reflections. (2) Student evaluation of ICE (the Intensive Clinical Experience).

[Qualitative data analysis]

A content analysis using a constant comparative approach was used to provide a basis from which a conceptual framework could emerge in relation to our research questions. Validity was assured by iterative consideration of the emerging explanations for the data. The number of times each code was evidenced in the full data set (Table 1) is given.

[Results]

The reflections were analysed and 40 codes assigned. The codes were merged into 11 sub-themes (Table 2) and from those, five themes were identified: communication; professionalism; team working; organisation of care; and student learning issues. Professionalism encompassed the greatest number of sub-themes and included reflections on the behaviour, professionalism and the quality of care given by all three professional groups. The most frequent code was ‘dignity, autonomy and patients’beliefs'(n=30).

[Discussion]

Guided reflection has a valuable educational impact on our students in the exploration of professionalism in a real work-based multi-professional setting. Reflecting on critical incidents encouraged students to understand and analyse professionalism, and recognize what it means to be a professional in the context of Duties of a Doctor.

Table 1. Frequency of codes.

—————————————-

Codes /Number of times evidenced

Dr positive communication /76

Dr negative communication /61

Teamwork positive /44

NHS/Social Services resources /33

Patient beliefs/autonomy/dignity resources /30

Dr/senior student limit of competence /12

Social Services respect /12

Social Services positive care /12

Confidentiality negative /12

Dr negative professionalism/quality of care /11

Nurse positive communication /10

Nurse negative care/behaviour/knowledge /10

Nurses positive care/behaviour /9

Respect (all professions) for patients & students negative /9

Student overcoming/acknowledging prejudice /9

Hospital negative communication /8

Dr interest of patient positive /8

Dr interest of patient negative /7

Dr positive professionalism/quality of care /7

Respect (all professions) for patients & students positive / 7

Patient or family decision? / 7

IP communication / 6

Culture/religion /6

Nurse negative communication / 5

Social Services negative communication / 5

Social Services negative care / 4

Racism / 4

Teamwork negative / 3

Power of doctors / 3

Students positive communication / 3

Dr positive behaviour / 2

Social Services ethics / 2

Student unease / 2

Institutional prejudice / 2

Social Services positive communication / 1

Dr up to date / 1

Communication problems language / 1

Student coping with death / 1

Sexism / 1

Student too much responsibility / 1

—————————————-

Table 2. Sub-themes.

—————————————-

Communication

Teamwork

Resources

Beliefs

Autonomy

Respect

Care

Competence

Confidentiality

Behaviour

Prejudice

—————————————-

Professionalism has been defined as: ’the extended set of responsibilities that include the respectful, sensitive focus on individual patient needs that transcends the physician’s self-interest,the understanding and use of the cultural dimension in clinical care, the support of colleagues, and the sustained commitment to the broader, societal goals of medicine as a profession’ (Hatem, 2003).

The learning objectives of ICE were:

. To encourage students to develop effective communication skills with patients/clients

. To enable students to meet, talk with and question professionals involved in health and social care

. To reinforce the Professional Ethical Code for Medical Students (University of Sheffield)

. To understand the Duties of a Doctor

. To enable students to reflect on experiences gained in ICE

開催日:2012年12月12日